Wireless Home NetworkingLesson 1: Networking without Wires

This lesson offers a brief introduction to wireless home networking: a short history of the technology, some ways it's being used, and a discussion of equipment and technologies that make it work.The World of WirelessUnless you haven't been paying attention lately, you've probably seen the term wireless networking popping up everywhere. You've probably visited a wireless cafe, or been able to work wirelessly at your office. It seems that wireless is the new big thing.

Historically speaking, wireless has been around for quite a while. Starting in the early 20th century, engineers figured out how to send radiotelegraph signals (Morse code) without the use of wires, making it possible for ships at sea to communicate with each other and with fixed locations on shore. With the discovery of amplitude, radio soon followed, and then came TV broadcasts.

Wireless applications are now found just about everywhere, from TV and garage remotes and two-way radios to digital pagers, GPS (Global Positioning System) systems, cell phones, and wireless networks. Wireless, the old term that used to mean radio, is now back in vogue.

This course introduces you to key aspects of current wireless technology, and specifically to how it pertains to setting up a wireless network in your home. This first lesson discusses the benefits of implementing wireless mobile technologies in your home. Wireless networking has a lot of promise, and for the first time in a long time, even technically impaired consumers can set up a home network without too much difficulty. Are you ready to work without wires?

Common Wireless StandardsBefore getting started, it'd be a good idea to define some general categories for wireless networking. Although the wireless landscape may seem bewildering, all you have to keep in mind is the following information:

- Wireless networking is about broadcasting (much like a radio station does) network data called packets over an airborne frequency.

- Similar to TV and radio, network broadcasts have an effective distance and certain materials or conditions (such as thick walls or rugged terrain) can disrupt broadcasts.

- Because wireless networking is a broadcast, anyone with a receiver tuned in to your network's frequency can see what you're doing, unless you encrypt your traffic.

That wasn't so bad, right? You're now ready to learn about the different specifications, focusing on the most popular ones.

802.11x

The 802.11x family of specifications is an extension of the Ethernet specification common in wired networking. The 802.11x family of specifications is flexible; it can handle TCP/IP (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol), AppleTalk, and other file sharing-based traffic. The most popular subspecification is 802.11b, which can be used in a heterogeneous computing environment (such as Macs, Unix workstations, and Windows-based PCs) as long as every machine is using 802.11b wireless cards and communicating via 802.11b access points.

802.11b can support up to 11 Mbps (megabits per second) at distances ranging from just a few feet to several hundred feet, transmitting over the standard 2.4 Ghz unlicensed band. Of course, as with other kinds of broadcasts, transmission distance is based on line of sight and obstacles, such as walls, appliances, and so on.

Newer protocols based on 802.11b, namely 802.11a and 802.11g, are also becoming popular. The 802.11a specification is much faster than 802.11b: It allows data transmission at 54 Mbps over the 5 Ghz (gigahertz) band. This is a great specification to use when sending huge files back and forth over the network, or when working with bandwidth-intensive network applications, such as streaming video.

The 802.11g specification is as fast as 802.11a but shares the same bandwidth used by 802.11b. It can transmit data at a rate of 54 Mbps over 2.4 Ghz. This is considered a next generation wireless network specification, and is designed for large enterprise installations and Wi-Fi (wireless fidelity) rollouts.

Bluetooth

Bluetooth is ideally suited for PANs (personal area networks) that operate within short ranges and need robust bandwidth support. Bluetooth is also a handy way to get your cell phone talking with a PDA (personal digital assistant), your digital camera transmitting data to a printer, and PDAs beaming information to a laptop. Similar to the 802.11b specification, Bluetooth broadcasts on the unlicensed 2.4 Ghz band. Although Bluetooth's bandwidth is much larger than 802.11b, its range is much shorter. Bluetooth is the perfect way to connect a peer-to-peer network, and is well suited to the task.

If all these different terms, categories, and specifications sound confusing right now, don't worry. You'll get into more detail about them as the course continues.

WLANs and PANs

In the last half-decade or so, you've probably heard and read a lot of hype about how wireless networking is going to change the way you work and live. Only now are some of these promises starting to come true. There's wireless access at airports, cafes, libraries, office buildings, even places such as Central Park in New York City. The way you work and play is even changing. You can now check your e-mail by turning on your wireless notebook while you wait in a client's lounge. Or you can break free from your desk and work from the comfort of a sidewalk cafe.

In wireless networking there are a couple of acronyms with which you need to be familiar: PAN (Personal Area Network) and WLAN (Wireless Local Area Network). You're probably wondering what these terms mean -- so let's talk about them!

Getting Up Close: PANs

PANs, as you recall, are personal area networks. These networks have a very short broadcasting range. So far the reigning champion in the world of personal area networking is the Bluetooth specification. Bluetooth allows mobile devices to recognize each other and communicate within a 30-foot radius. Bluetooth cards are available for PDAs, notebook computers, printers, digital cameras, and other devices. What's nice about Bluetooth isn't just its wide availability: The cards are relatively inexpensive and don't require a huge power source to run.

How would you use a PAN in your home? Imagine that you're taking photos at your son's eighth birthday party with your Bluetooth-enabled digital camera. Instead of walking back to your computer every hour or so to download the images, you can send the images over the PAN to your desktop computer, which is also Bluetooth-enabled.

Or, imagine that you want to print some notes you took on your Palm device. Instead of synching the data with your desktop PC and then sending it to the printer, your Bluetooth-enabled Palm device can print directly to your Bluetooth-enabled printer.

You may also have a wireless PDA and cell phone combo, both of which have Bluetooth cards. You can use the Bluetooth connection to allow the PDA to send e-mail via the cell phone's connection to the Internet -- without having to tap out messages using the phone's keypad, or even take the cell phone out of your bag.

Think Local: WLANs

The 802.11x family of WLAN specifications take wireless beyond the realm of PANs. With a well-designed WLAN, people working in offices or at home have added flexibility over where they access the network.

For example, instead of sequestering yourself in a back home office, you can choose to work in the living room, closer to the rest of your family. Or you may choose to check your e-mail or crunch the family budget from the comfort of your patio on a beautiful day.

The rest of this course focuses mainly on setting up a WLAN in your home, so you'll learn more detail as it becomes appropriate.

The Big Picture: An Overview of a Typical Wireless Home Network

Generally speaking, up until a few years ago, most homes had just one computer in them, with one set of peripherals, such as a scanner and printer used by that computer. Because there was only one computer, there really wasn't much need for sharing those peripherals or communicating with other machines on a network.

It soon became common to see more than one computer in a household. Rather than buying extra scanners, printers, and other devices, homeowners could hook computers together with hubs and Ethernet cables, and share those devices. If your kids had to print a report for school, they could do so by sharing the printer in the den.

Also, more and more professionals started to bring work home on their laptops, and needed easy access to the Internet. Added to all this activity was the burgeoning work-from-home workforce of telecommuters, consultants, and freelancers. All of these users needed a flexible, inexpensive solution that allowed for the creation of networks.

Instead of having to worry about running cable from one room to the next, wireless technologies allow for an elegant solution. All you need to do is:

- Buy a wireless access point and attach it to your outgoing cable or DSL modem/router.

- Buy wireless cards for each computer on the network.

- Buy wireless cards for each peripheral you want to share, or simply share the peripheral on the network.

That's it -- that's all you need to set up networking. Wireless provides a cheap way to get set up, and also offers inexpensive ways of growing your network if you need to. In upcoming lessons, the necessary components are covered, and you'll learn about network security.Moving On

In Lesson 2, you find out about the major categories of wireless gear. But before moving on, be sure to visit the Message Board to see what other students are up to.

Lesson 2: Access Points, Routers, Hubs, and Cards

In the first lesson, you learned about the world of wireless standards -- what frequencies are used, distances involved, and other general topics. In this lesson, you learn about the different components of a wireless networks; in other words, the gear that actually uses the standards and frequencies you learned about in Lesson 1.

For the purpose of setting up a home network, all you need to worry about are two major categories of components:

Gear that creates the wireless network and connects you to the Internet

Gear that allows individual machines and devices to connect to the established wireless network

The following sections discuss access points, routers, and hubs. These wireless components enable you to establish a wireless network.

Access Points

An access point (or gateway) does exactly what its name implies: It provides a point through which your machine can access a wireless network. Generally speaking, an access point both transmits and receives data on a wireless network, so technically it's a transceiver.

An access point can connect wireless users, and forms the interconnection or bridge between wired and wireless networks.

For very small WLANs, such as those used in small offices or homes, one access point is usually all that's needed. As your network grows in physical size (such as distance in feet or meters) and number of users, you'll need to think about multiple access points. If you run into this situation, you need to make sure that your coverage overlaps so that you don't lose users in dead spots.

WARNING Network design is covered in the "Planning Your Home Network" section later in this lesson.

Wireless access points run from $100 to $450, and usually have a maximum range of 300 feet indoors, and 1,500 feet outdoors.

Routers

If you want to connect to the Internet, you need a router to do so because wireless networking is known as local area networking -- local as in connecting devices local to you. The router sends Internet traffic to the Internet site while keeping local traffic between your own computers on your home network. If you have cable modem, DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), satellite, or other broadband service in your home, you likely have a router or modem set up already.

In most cases, you can connect your router to an access point, walk through a simple configuration process, and presto, have connectivity to the Internet via wireless and wired networks.

Hubs

A hub is similar to a router, except that it doesn't have as much brainpower. Your typical hub for home use has four or eight Ethernet ports that allow you to connect multiple machines. Hubs can connect your home network but they do not route to the Internet. You might need a hub if you hook your router to more than one wireless access point; however, in many cases the better wireless access points have a hub built into them.

Wireless Card

Having a wireless access point isn't enough. You need to be able to connect to the wireless network. Every machine needs to have a wireless card. Wireless cards are devices that fit into a PCI (Peripheral Component Interconnect) slot for desktop PCs, or PCMCIA (usually called PC Card) slots for notebook or laptop computers and transmit and receive wireless broadcasts. Most wireless cards transmit on a particular frequency determined by the standard it supports, such as 802.11b, and cost anywhere from $50 to $150.

Wireless cards for desktop machines are designed to fit into one of the empty PCI slots found inside the computer. To install one, turn off your computer, remove the cover of the machine, slide the card into an empty slot, and then follow the instructions for configuring the hardware. Although manufacturers are starting to include wired Ethernet cards standard, wireless networking cards aren't as common.

Wireless PC Cards for notebooks and laptops fit into a PCMCIA slot, usually found on the left or right side of the machine. Unlike desktop PCs, many new laptops and notebooks are shipping with wireless cards already built in

When you purchase wireless cards for your computers, make sure that the cards support the same standard and broadcast frequency as the wireless access point. The 802.11g standard supports the older 802.11b cards but 802.11b cards will be slower than an 802.11g card. Standard and frequency should always match. There's no need to buy the same brand wireless card and access point. The following table lets you which cards to buy with which access points.

Table 2-1: Access points and cards.

Access Point Card

802.11a access point 802.11a cards only

802.11b access point 802.11b cards only

802.11g access point 802.11g card preferred and 802.11b

Plan Your Home Network

At this point, you might be thinking to yourself, "Hey, this wireless networking thing doesn't sound too bad! Just buy an access point and some wireless cards, and start networking without wires."

In a way, you're right. But even the simplest wireless network implementation can hit snags if you don't do some planning beforehand. For example, you might place the wireless access point in your corner office, too far away to get a great signal out on the patio and thereby dashing any plans you might have to work outdoors on beautiful spring days.

Although there are many techniques available for planning a wireless network, a good simple technique involves asking some common sense questions, such as the following:

- Who and what: Who'll be using the network and what they'll be doing on it? This isn't just a list of people, but a general idea of the kinds of applications they'll be using on the network. If you're working from home on a big project that requires Internet access, you might get bogged down if Johnny's playing a graphics-intensive networked game with three of his best friends.

- Where: Where do you want to access the network? For most homes, one access point is enough to provide coverage in any room -- and even limited outdoor areas. However, very thick walls, maze-like hallways and staircases, and any metal obstructions, such as metal shelving and steel pillars, can obstruct broadcasts. If you have a separate building on your property in which you want to access the network, you may find yourself outside broadcast range while in that building, or at the very least with a weak signal.

- When: As in when users will be on the network. Even a small group of users performing bandwidth-intensive tasks all at the same time can bog a wireless network down.

- How: How packets are transmitted -- in the clear or encrypted? Encryption and other security measures add overhead to network connections, which can slow you down. Security is covered in Lesson 3.

This is just a beginning, of course, but with these issues in mind, you can start planning for an ideal home wireless network, one that meets your needs and grows as you need it to.

Common Networking Terms

Before we go any further, we should probably spend some time talking about some of the networking terms you're likely to hear, especially now that you're almost ready to go out and buy gear.

The most common terms you'll hear revolve around the nature of networking include:

- Bandwidth: Refers to the speed of the network. It's a term that refers to the size of the network pipe through which your data travels. Generally speaking, the more bandwidth you have, the better your speed is. Things that can affect bandwidth include number of users on the network, types of traffic on the network (big multimedia files will slow down a network), and availability of routers and access points.

- Availability: Refers to the availability of the network. If the network is always down, it isn't very available. You should always strive to run a high-availability network. In wireless networking, distance from an access point can affect your network's availability, because the broadcast signal deteriorates with distance.

- Packet: Data sent over a network is sent in packets. Each packet has a header and a payload. The header helps identify the packet as part of a message, and the payload carries actual information (such as a piece of an e-mail, a part of an image, and so on).

- Mbps (megabits per second): Refers to how the speed on a network is measured and is used to describe the bandwidth. A 10 Mbps network connection allows you to send data at the theoretical rate of 10 megabits per second. I say theoretical because a network connection is just like a highway or road. One might say that a certain road can carry up to 500 vehicles per minute, but placing that many cars on the road would make for a very congested road. The more congested the road, the less useful it is, and the slower the traffic goes. Same with a network. If you share a 10 Mbps wireless connection that's fully utilized, what you'll end up with is a very slow connection -- it's literally bogged down with data packets.

TIP To ensure that a computer has the fastest connection, locate it as close to the access point as possible.

- Protocols: Data packet transmission is governed by protocols, which are nothing more than rules that dictate how data travels on a network, how it's structured, who can accept what data, and how data receipt is acknowledged.

- TCP/IP (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol): The most common protocol for transmitting and receiving data. TCP/IP works by breaking data into hundreds or thousands of individual packets and sending them across the network. Although breaking up your information into lots of different packets, sending them across the network and putting them back together at the destination might seem like a big waste of time and energy, its actually incredibly fast and efficient.

- LAN (local area network): One of the two types of networks. LANs are small networks that cover a small area; in other words, your wireless home network.

- WAN (wide area network): A network that connects two or more LANs with the public Internet or some remote network. We don't cover WANs at all in this course, but in the last lesson, we cover connecting to your company's LAN from your home network using a VPN.

- VPN (virtual private network): An encrypted tunnel through which you can send e-mail, files, and other data. VPNs are very useful because they allow different organizations separated by great distances to be part of one big WAN using the public Internet. Because all traffic in a VPN is encrypted, only those users who have the decryption key can read the traffic. That way, VPN users can take advantage of connectivity using the Internet and feel secure that only those users who should see network data are seeing it.

Moving On

This lesson covered some of the basic gear and terminology you'll need to set up your wireless home network. Now, refer back to the answers you gave for the questions in Assignment 1 and get ready to do some hard thinking and shopping with Assignment 2. Don't forget to take the quiz that goes with this lesson.

Lesson 3 covers a very important topic -- security. But before moving on, be sure to visit the Message Board to see what other students are up to.

Lesson 3: Sharing and Security

Introduction to Sharing and Security

Setting up a wireless network is designed to be easy. If you followed the first two lessons and assignments, you were probably able to set up your own home wireless network in no time. Quite possibly, the hardest thing to do was to pick out the right gear.

Although setting up a wireless home network might have been a snap, your new network might not be secure. Unlike normal wired networks, wireless networks broadcast data packets -- your information -- out into thin air where anyone can pick up the broadcasts and see what you're doing.

The last thing you want is for someone to be able to peek into your private life and find out information about you, such as what you're doing online, what you're buying, what files you have, where you do online banking, what credit card numbers you use, what your passwords are, and so on.

Unfortunately, the very nature of networking is in sharing what you have: data, printers, file systems, and all the rest. Otherwise, you'd be back to where you were before -- handing other people disks or CDs full of files or buying separate printers for everyone in the house. As much as a convenience as a wireless network is, you have to think about restricting access to it.

This lesson talks a bit about how to share information and services throughout your network, and then discusses how to secure the network. That way only the people you approve of can access your network.

Configure Your Network

Now that you've planned your network, bought all the gear, brought it home and installed it, it's time to get your machines on the network. This lesson assumes that you're working on a Windows XP machine.

TIP: Your steps may vary depending on the version of Windows your using, but they should be similar.

The following steps work on Windows XP, with the Control Panel set to XP View (not Classic):

- Select the Start button, and then click Control Panel.

- Click Network and Internet Connections.

- Click Set up or change your small office or home network.

- Follow the wizard's instructions. Be sure to use the same network and/or workgroup name on each machine.

That's all you have to do. To test your network, simply click the Start button on any machine, and then click My Network Places. You should see a list of other machines on your network, such as //dad-computer/shareddocs/. If you double-click any of those listings, your computer should take you to that shared folder.

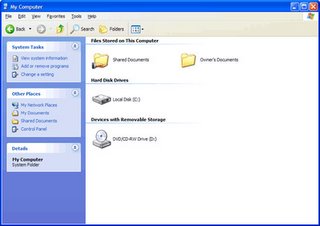

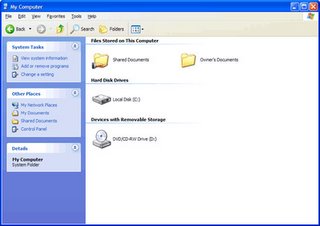

Set Up Shared Folders

The easiest way to share information on a wireless network is to set up shared folders on your machine. If you're running Windows XP, notice that you have a Shared Documents folder in the My Computer window, as shown in Figure 3-1. This folder is set up as a shared resource -- whatever files you place in it can be seen by other machines on your network.

Figure 3-1: The Shared Documents folder.

Figure 3-1: The Shared Documents folder.

When you look at this folder, you can tell it's shared because it has an icon of a hand underneath the folder (a hand stretched out sharing something).

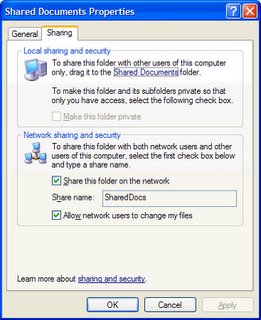

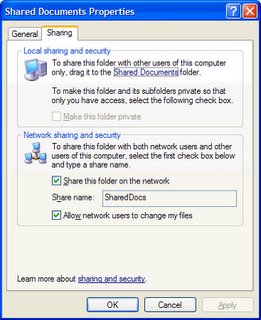

Right-click the Shared Documents folder, choose Sharing and Security from the context menu, and click the Sharing tab to see the different options for the folder.

For example, you can set the folder's name on other computer's displays -- in other words, the name that other users see when they view your Shared Documents folder from across the network. (In Figure 3-2, that name has been set to SharedDocs.)

In most cases, it's okay to leave the name of the folder to its default. In other cases, you might want to give descriptive folders names, such as FamilyTripPhotos. Remember that on a wireless network, names of shared folders are broadcast into thin air; unless you secure your network, unintended people such as your neighbors can see your folders.

WARNING: It's generally not a good idea to share folders that contain personal information, such as family budgets, credit card information, passwords, work files, or personal e-mail.

You can also allow other network users to make changes to files in this folder. This enables other users to add, delete, and change files in this folder. In Figure 3-2, the Allow network users to change my files option is checked because the owner of that particular machine knows other network users will need to update the files in the folder.

Figure 3-2: Configuring sharing from the Shared Documents Properties dialog box.

Whenever you share a folder, it's usually a good idea to share only folders, not your entire hard drive or big sections of your hard drive. You don't want network users, generally speaking, to be able to access your entire machine -- just small parts of it.

Share New Devices on the Wireless Network

You can share devices of all kinds on a network, and it's just as easy as sharing folders. All you have to do, generally speaking, is right-click the device icon, and then choose Sharing and Security from the context menu to share that device.

What kinds of devices can you share? You can share all of the following, plus more:

- Printers

- Scanners

- Digital photo card readers

- External hard drives

- Zip drives

Use Encryption and Passwords on Your Network

When talking about security for a wireless network, you have to think about two main threats:

- Internet-based threats

- Wireless-based threats

Internet-Based Threats

The first type of threat involves someone on the Internet getting access to your home network by slipping through your ISP's (Internet Service Provider's) routers or firewalls and copying, damaging, taking over, or changing your files or systems. Although this may seem like a remote possibility, you could be a candidate for malicious behavior if you are:

- A highly-placed executive in government or business who brings work home

- A public persona or celebrity in your town or area

- A person of means or wealth (even if it's just perceived)

There's also a good chance that you may be randomly targeted by someone who doesn't even know you.

In any case, your first line of defense from an Internet-based attack is your ISP. They should have routers and firewalls that block your machine's IP (Internet Protocol) address (your unique address on the Internet) to keep attackers from targeting you directly. Your ISP should also be monitoring all Internet traffic to make sure nothing malicious is happening.

If an Internet-based attacker does get through, you can prevent further damage or harm by installing a personal firewall on each machine in the network. Although this may seem redundant (after all, your ISP is probably running a firewall, too), personal firewalls can keep some bad things from happening.

Wireless-Based Threats

A more likely threat is someone accessing your wireless network directly. Unfortunately, this can be as easy as someone driving around neighborhoods with a wireless laptop trying to pick up available broadcasts. (This activity, by the way, is called war driving, which is similar to the much earlier practice of war dialing -- using a computer to call all numbers on an exchange to see which ones were faxes, modems, and other exploitable devices.)

After gaining access to your network, a war driver can do any number of activities, including:

- Add, edit, or delete files

- Snoop on your traffic (to pick up your credit card numbers and other sensitive information)

- Surf the Internet on your dime

- Perform malicious attacks on Web sites and make it look as though you did it

Now that you've thought a little about all of that, it's time to break down what you must do, what you should do, and some additional little tricks to secure your network.

Security: What You Must Do

Make sure that you change the administrative password on your wireless access point. It's well known, for example, that Linksys access points ship from the factory with admin as the password. The IP address of these access points on an individual network is also well known. Anyone sitting in front of your house could easily take over your network because of this.

After you've done that, disable remote management of your access point. This keeps folks on the Internet from slipping in and trying to mess with your access point.

Next, turn off SSID (Service Set Identification) broadcasting from your access point. Although SSID makes it easy for anyone to set up a laptop for some fun wireless gaming, it also allows anyone out there to pick up your broadcast and join your network.

Last on the list of things you must do is turn on WEP (Wired Equivalent Privacy). It's not perfect (it has many documented problems and holes), but it's better than nothing. It involves setting a 64-bit or 128-bit encryption key on your access point or router. Any machine that wants to be part of that network must enter the key to join.

You can find out more about WEP online by visiting the 80211 Planet article: 802.11 WEP: Concepts and Vulnerability.

Generally speaking, the longer your encryption key, the more time it takes to encrypt and decrypt traffic on your wireless network. Security experts use the term overhead to describe encryption's effect on general network speed. Although 128-bit encryption effectively doubles overhead as compared to 64-bit encryption, network speed is still fast with either.

TIP: Very good hackers can usually break these kinds of encryption keys with off-the-shelf tools, but the idea is to make your wireless network less appealing as a target.

You usually have two choices for creating encryption keys:

- Typing in a series of hexadecimal or ASCII numbers/letters (such as AfAfB6c3D1)

- Typing in a passphrase (such as retired us military) that then generates a set of keys

WARNING: Don't use the preceding key or passphrase now that you've seen them published here; so has the hacker community!

After you have a set of keys, you need to add it to every machine on the network. You can do this by right-clicking your wireless connection (usually visible in the system tray in the lower-left corner of the screen) and adding it to the network key field.

Security: What You Should Do

If you've followed the previous advice, your home network is more secure than 80 percent of home wireless networks (percentage based on study conducted by a hacker group). Still, there's no rest for the wicked. This section covers some other actions you should take to make your wireless home network even more secure.

- Set up MAC-based security: The MAC (Media Access Control, not the Apple type of computer) layer is about Ethernet cards, physical machine addresses, and devices. Some routers and access points allow you to set a range of allowable MAC addresses on your network. Although this can become a big management exercise on a big network, it effectively allows only those machines you want.

- Disable or limit DHCP: DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol) allows machines to get their own IP addresses after they join your wireless network. This can be handy for adding new machines to the network, but can also make it easier for your friendly neighborhood war driver to exploit your network.

Some ISPs require that you keep DHCP running at all times for management purposes. If this is the case, you might not be able to implement this change. If that's the case, ignore the next point.

- Don't use the default IP address range provided by the equipment: Most routers or access points ship with a built-in 10.1.1.x or 192.168.1.x network. The first machine on the network is given a .1 address (such as 192.168.1.1), the second machine, a .2 address, and so on. See how easy that is to guess? But a default starting network of 10.232.5.x is a different story.

Security: Other Tricks

The following are some other tricks you can do to boost your wireless network security:

- Change your SSID every few months. This can be annoying and tedious because you have to change it on your access point and every machine that uses the network.

- Change your encryption key every few months. Ditto on the annoying and tedious.

Keep your wired and wireless LANs segregated, each with their own firewalls or routers that only funnel appropriate traffic. You have to worry about this only if you have a fairly large network at home.

- If you want to be sure that you're secure, buy a program such as NetStumbler and try to hack into your own network. This process can uncover all kinds of possible vulnerabilities and exploits.

Moving On

This lesson covered some important points to help you make your wireless home network more safe and secure. It also explained how hackers can gain access to your network.

Lesson 4 discusses more advanced networking topics.

Lesson 4: Advanced Networking Topics

Expand Your Network

If you've gotten this far, you've accomplished a great deal, such as:

- Planned your wireless home network

- Purchased, installed, and configured all the gear

- Secured your network and shared folders and devices

This lesson covers some advanced topics related to growing your network. Although your network might be small now, at some point, you might need to add machines or expand the broadcast coverage.

Sooner or later, you'll need to expand your network. You'll either have added so many users and machines onto your network that it starts to bog down; or you'll experience big changes in the kinds of files you send over the network; or you'll need to expand broadcast coverage to additional parts of your home.

Fortunately for you, expanding a wireless network is a simple matter. In most cases, all you have to do is buy more wireless access points to increase your bandwidth and coverage. In some cases, however, you might be able to take other steps, such as establishing routers and servers.

Add More Access Points to the Network

The simplest way to expand your wireless network is to set up additional access points. This is particularly effective if:

- You have users you can keep on separate access points -- for example, you might put your kids on one access point, and keep the adults on a separate one.

- You have different parts of the property that need coverage -- for example, the third floor of your home is an office that needs coverage, you also need coverage in the kid's bedrooms on the first floor, and you like to work in a converted shed out back.

When you buy additional access points, make sure that they all use the same wireless protocol, such as 802.11b, and be sure to set up security on each one. For those machines that might roam between different wireless coverage areas, such as a laptop, you need to configure the laptop with each wireless access point's encryption keys.

You need to set the same SSIDs (Service Set Identifications) on each additional access point if your laptop or other device will roam and use multiple access points. The SSID identifies the WLAN (Wireless Local Area Network); for example, linksys is the default SSID for most Linksys products. Although you may have overlapping network coverage when you have more than one access point, in reality, a machine will only communicate with the access point with the strongest signal.

To avoid cross talk on overlapping wireless access points, set different broadcast channels. It's also a good idea to choose channels that are noncontiguous. If your first access point is broadcasting on channel 1, set your second wireless access point to broadcast on channel 6 or 10.

Any laptops or other devices that roam from area to area will lock on to the strongest broadcast they discover.

Other points to consider when adding more access points include the following:

- Most access points have an effective indoor range of 150 feet -- less if there are obstructions, metal shielding, or thick walls present. You want only a little bit of overlap (several dozen feet at most) because otherwise you're just wasting effort.

- Although wireless access points placed near the center of your home (or in your basement or attic) might be invisible from the street, access points placed near the periphery of your home can likely be picked up. Always put security measures in place.

- When the day is done, your speed on a wireless network is determined by two main factors: distance from the access point and number and quality of obstructions between a system and an access point. Even slight changes in the way you point your laptop or even raise the height of a wireless access point can mean dramatic changes. Some users have reported great returns by keeping antennas straight or even replacing shorter antenna with longer ones.

- As has been mentioned before, wireless networking involves broadcasting packets into thin air. With the 802.11b and 802.11g specifications, you have only 11 channels on which to broadcast and these overlap. To ensure that you have unique channels with no overlap, you should choose from channels 1, 6, and 11. 803.11a has 12 channels to choose from.

- Make sure that other appliances or devices don't broadcast on this frequency. These appliances and devices include microwave ovens, many cordless phones, some power lines, Bluetooth devices, and neighbors with their own 802.11b networks.

Add a Router to the Network

You can possibly alleviate growth problems by setting up a router and keeping traffic on its own subnetwork. For example, if you play wireless LAN games, the data traffic might bog down the entire network. If you can keep all of this traffic (which is mostly localized) on one subnetwork, users on other subnetworks may not be affected.

Most routers support the creation of different subnetworks. Because each model has different settings and commands, read your particular router's documentation to set up different networks.

A router can also be an effective way to secure different parts of your home network. For example, you may restrict certain types of traffic on certain subnetworks (such as only e-mail and Web traffic).

Add a Simple File Server to the Network

You might find yourself in a strange situation: You have a wireless network, each machine sharing lots of documents. It gets harder and harder to keep track of where different files are at. Different users notice that when they share directories, their machines bog down a little when many other users start using files. This might happen if you're sharing a lot of music files.

The answer to this problem is setting up a simple file server on your network. A file server is a dedicated machine that holds files and other data needed by a group of network users. Although it may seem like a pain in the neck to buy, install, and set up a separate system, in some cases (such as doing periodic backups) it gets easier to work with just one system.

Options for Setting Up a File Server

Several options exist for setting up a file server on your home wireless network, including the following:

- Keep your old laptop or desktop that has been replaced by a newer model. Take out all the applications and programs, and leave just the operating system. If it's a Windows machine, add it to the network, share the My Documents folder, and allow all users to make changes to this folder.

- If you have more time and expertise, you can install the Linux operating system on a machine and then set up an FTP (File Transfer Protocol) area. FTP directories on a Linux machine usually require usernames and passwords every time you want to upload or download files, so they're more secure.

- Another easy way to set up a file server is to buy an USB (universal serial bus) 2.0 external hard drive and share it from one of the systems already on the network. Although not quite as fast as having a separate file server, it does provide a place to store and retrieve valuable or much-needed information. Many models come in 20, 40, 60, 80, and even 100 GB storage capacities and can be connected to create larger storage areas.

Add a Print Server

When you first started out with your home wireless network, sharing a printer on a network is probably all you need to get work done. At some point, however, you may need to provide more access to your printer.

What you need is a print server. Generally speaking, there are many ways to share a networked printer, including the following:

- Buy a printer with a built-in print server: These printers are usually expensive, but they can handle many print jobs. They offer security, reliability, and can queue an impressive number of jobs.

- Buy a wireless print server: You can connect your printer (or printers) to one of these gadgets (they usually run around $250) with a standard parallel, USB, or Ethernet cable, and use the wireless print server to broadcast the printer's availability to other machines on the network.

The second option, using a wireless print server, is much faster and cheaper. Most wireless print servers for the home can usually handle up to three printers, which make them the right size for the job. The combination of wired access to the printer over a wireless network gives you the best of both worlds -- wireless access and the speed of a wired connection.

Decide When to Expand

Knowing when to expand your network is just as important as knowing how. A standard 11 Mbps wireless connection can usually handle the following kinds of network load:

- 40-50 users that normally stay idle and don't do much beyond occasional e-mail

- 20-25 who are moderately active, especially in uploading and downloading moderately sized files

- Up to 10 power users who are constantly active on the network, using several applications, and/or transmitting large files across the network, such as large pictures, audio, video, or documents

Although you may never bump up against any of these networking constraints in a typical home environment, you may need to add more access points if you run a home-based business or host large LAN parties.

Cool Tricks for Expanding Your Network

Okay, so you've set up a home office with a shared printer, maybe an external hard drive and a wireless printer -- maybe even your own print server. You might even host monthly LAN parties and have all your friends come over for a friendly night of shoot 'em ups.

But what if you really want to take this wireless networking thing to the extreme, such as hooking up all of your computing gear to your home entertainment gear?

With just a few hundred dollars worth of equipment, you can easily set up a TiVO-style system that records your favorite TV shows (either analog, broadcast, digital cable, or satellite) onto a hard drive. You need to upgrade to an 802.11g wireless network (802.11b is too slow for full-spectrum video) and plenty of storage space (30 minutes of video is about 150 MB). After you have the captured video, you can share it, edit it, delete it, view it, and more. You can even view TV signals on a laptop equipped with a TV tuner card. With the right equipment, you can also control your TV from a wireless laptop.

Do you have a bunch of MP3 files stored on a computer or laptop and want to play them on your home stereo? Well, most sound cards come with a 0.125-inch jack for headphones. Simply run down to your favorite electronic superstore and buy a cable with a 0.125-inch plug on one end and two RCA connectors on the other end that plug into the line-in jacks on your audio amplifier.

If you want the same thing without wires, kits are available starting for around $100 that will let you beam music files to your home stereo equipment from a PC or laptop. Bingo, music to your ears.

Moving On

This lesson discussed the different ways you can expand your network. It also covered when you might need to expand, and the best ways to do so. The next lesson goes over some troubleshooting topics.

Lesson 6: Wireless for the Home Office Worker

The Wireless Work Attitude: Be Free

You've finally done it. You were able to convince your boss to let you work from home one or two days a week. Or you were able to keep your job in the same city although the rest of your department moved three states away. Or you decided to bag the entire corporate scene and become a work-from-home consultant.

You feel free. You have energy that you didn't have last week, last month -- heck, for the past six months. What a feeling not to fight that dull, long traffic snarl between your house and your office.

Now all you have to do is figure out how to become as productive at home as you are in the office, and wireless networking can be a huge part of that. This lesson walks you through all the different aspects of working from home -- as a telecommuter, consultant, or freelancer -- in a wireless environment.

This lesson makes some assumptions:

- You have one or more computers and peripherals in your home network.

- You have broadband access to the Internet.

- If you're a telecommuter, you need to connect to certain proprietary networks.

- If you're a consultant working with sensitive customer data, or if you're a telecommuter, you need to use encryption.

First and foremost, keep in mind that working in a wireless environment means that you can start thinking outside the box. If you're not tethered to an Ethernet cable, you can reconfigure your office. You might be able to move your desk closer to the den window, or into a different room in the house. If you have a laptop, you can choose to work outside on beautiful days, or even visit a wireless cafe and do your work there.

The idea is to be free. But, paraphrasing the Amazing Spiderman, with great freedom comes great responsibilities. One of the most effective parts of working in a work-like environment is your ability to focus on work. By freeing yourself from the tethers of an office-like environment (even one at home), the lines between work and play can start to blur.

A little bit of blurring might be fun. Just moving your laptop out to the back patio can increase your creativity, problem-solving abilities, and productivity. There's nothing like a change of venue to clear the air.

Too much blurring and you start breaking down all the advantages that make a work environment so productive -- without any of the benefits of increased creativity from a new environment. For example, you might find yourself surfing the Web, or slipping in a video game instead of writing that report, just because you can. After all, it was the "just because you can" idea that got you out on the back patio in the first place.

There's another hidden drawback to being always on, and it only becomes a problem after you've established a solid working pattern. If you work from home, you need to draw clear boundaries between your work and personal lives. Just because you can check your office e-mail at any time of the day or night doesn't necessarily mean that you should.

Failure to draw boundaries on your work activities can quickly turn your wireless home network into a burden, not a tool. You might get to the point where you dread going into your office for fear of seeing more e-mail requesting urgent action. You won't even want to go into that space for recreational purposes, and this can be a bad thing.

If you find yourself feeling dread over your home networking setup and how it impacts your personal life instead of feeling good about how much more productive you are in your work, it's time to consider some clearly defined boundaries.

Another boundaries-related issue you need to confront is your home life. When you're working, you need to send a signal that you're working. If you stop to run errands, play with or baby-sit the children, or walk the dog, you may be sending the kind of signal to your family that says "It's okay to bug mommy or daddy when they say they're working."

What they won't understand is time spent with them (or doing things for them) during the day needs to be made up in the evenings and possibly weekends.

If, on the other hand, you establish clear boundaries for your office (whichever room it may be) and some regular office hours (8:00 to 11:30 a.m. and 1:00 to 5:00 p.m., for example), you can keep your productivity high and achieve a more positive work/life balance.

Here are some quick tips for establishing some boundaries:

Rules for your family:

- Unless something is urgent, don't interrupt.

- Knock on the office door before entering.

- Don't answer the business phone.

- Keep noise levels down during work hours, such as keeping the TV and stereo volume low.

- Control noisy pets.

Rules for you:

- Wear professional attire when you go in to your at-home office. Studies show that at-home workers are much for focused and business-like when they're in appropriate dress.

- Establish a set routine. For example, whenever possible, do your creative work in the morning, make your calls after lunch, and attend all meetings in the late afternoon.

- Answer your business phone professionally with your company name and title.

- No TV, stereo, recreational Web surfing, and video games during work hours.

Security Issues

If you're working from home, security is going to be a top priority. You might be working with sensitive information belonging to your company (if you're a telecommuter) or your clients (if you're a freelancer or consultant).

Security for Telecommuters

If you haven't instituted any of the security measures discussed in previous lessons, your company will probably make you use most of those precautions -- and more besides. Typically, you might have to deal with:

- Working with a VPN (virtual private network ). A VPN is basically an encrypted tunnel through which your data can pass. A VPN connects two endpoints, usually the system you're on and a corporate server. VPNs allow companies to extend their network out to geographically dispersed systems -- in other words, remote and home offices.

- Using a smart card. Smart cards usually look similar to a calculator, and are designed to generate one-use passwords. They usually have a keypad and a small LCD display. You punch in your assigned PIN and then the smart card displays a password. You generally have about 30 seconds to log in using special software and enter your newly generated password. Each time you log in to the system, you have to use a newly generated password.

- Installing a firewall. Different companies have different policies regarding the use of firewalls. Some may suggest that you install personal firewalls only on the system with which you work, and others may demand that you set up a network firewall (doubly so if they find out you're wireless).

- Firewalls act like a choke point. They can be set up to reject or accept different kinds of traffic such as e-mail, Web, FTP (File Transfer Protocol), telnet, and they can disallow network connections from individual machines or networks. Some firewalls can be configured to filter out certain content, such as adult-oriented material. What these filter out depends largely on the company's policies.

- Installing and keeping an up-to-date virus scanner or shield. Virus scanners not only protect you from picking up the latest destructive computer viruses, but they can keep you from spreading them unwittingly to other coworkers.

- Regular scanning and removal of spyware tools, cookies, and other programs. Spyware tools can be added to your system without your knowledge just by visiting Web sites or accepting e-mails from unknown companies. The primary use of spyware is to send information about your online habits back to a collection unit. Information that can be collected includes e-mail addresses, URLs, even passwords and credit card numbers.

One of the best programs available for getting rid of spyware is SpyWare Search and Destroy. Best of all, it's free.

- Implement physical security for your systems. By physical security, most companies don't just mean "is the door to your office locked." They also mean that you should have boot passwords for all computers, screen-saver passwords, and other precautions. All of these physical security measures are meant to make it harder for your equipment to be stolen or broken in to.

- If you travel a lot, there are systems you can place on a laptop that will sound an alarm if the laptop moves more than 20 feet away from you. This is more than handy if someone tries to snatch your laptop bag while you're waiting in an airport security line.

Security for Consultants or Freelancers

If you're an at-home consultant or freelancer (and if you are, you're in good and growing company), you probably won't have any strict or formal security requirements placed on you. However, it's probably a good idea to start implementing some basic safeguards to keep information about your clients confidential, such as:

- Start with physical security. Enable boot and screen-saver passwords on your desktop and laptop computers. By doing so, all information on those systems stay somewhat safe if they are stolen or broken into.

- regular backups of client data, and make sure that the backups are encrypted. Also, if the backups are on removable media, such as tapes or CDs, place those backups in a locking and fireproof file cabinet or safe.

Data backups can also help you rebuild your business-related data in case of theft, corruption, or viruses.

- If you're in the IT business, consider using more industrial-strength tools, such as encryption keys for e-mail and SSH (secure shell), instead of telnet when connecting to a remote machine.

- Encrypt anything confidential about your client. Many Web consultants have access to their client's system passwords, ecommerce settings, and even banking information. If any of this information falls into the wrong hands, it could mean untold grief for you.

- Use professional-grade deletion software to clean up files on computer systems. Just deleting files or sending them to the trash or recycle bin often does not completely remove files. Part or all of deleted files can stay on a computer system for years and years. You wouldn't want an old laptop you sell to someone else to give away your customer's secrets, right?

Although most of these security measures may seem like a pain or hassle, they're all part of what a professional consultant does to safeguard his/her client's data. Remember, safeguarding client data is the same thing as safeguarding repeat business.

Security Resources

One of the best places on the Internet for downloading security software is CNET's http://www.download.com/. You can browse the listings and get spyware scanners, virus scanners, and even network sniffers and personal firewalls.

If you want more in-depth knowledge about security, you need to read some white papers and case studies. You can find some excellent ones at the following Web sites:

At all of these Web sites, you can use search terms such as wireless networking, or browse through a category tree to retrieve different documents. You might see many of the same white papers repeated, but these Web sites give you the big picture of what's happening out there in the world of wireless security.Moving On

Congratulations! You're done with this course. At this point, you should know more than enough to plan a home network, purchase the right gear, install it, and get working (or playing).

Good luck with all of your wireless home network adventures!

Figure 3-1: The Shared Documents folder.

Figure 3-1: The Shared Documents folder.  Figure 3-2: Configuring sharing from the Shared Documents Properties dialog box.

Figure 3-2: Configuring sharing from the Shared Documents Properties dialog box.